I've Never Campaigned Against Anything. I've Always Campaigned for Something

I met Richard O’Neill on a sunny July day near his home in the northern English market town of Bury, about a 40-minute tram ride away from Manchester. He had been in contact with the Roma Peoples Project since April, when he wrote to commend our Newsweek article on the need to re-think the Gypsy stereotypes associated with Notre Dame.

As we communicated across the Atlantic, the RPP team was struck by the optimism with which he approached Roma activism and his commitment to writing new representations of Roma across a variety of media. We were intrigued by his poetic writing and storytelling, and we wanted to know more about him.

When I went to England in July for my PhD graduation from Durham University, I made a point of meeting him in person and hearing his story. I took the train up from London and then got the tram from central Manchester to Bury, where Richard met me at the station. We sat in the sun at an outdoor cafe near the Bury market, and he told me his story.

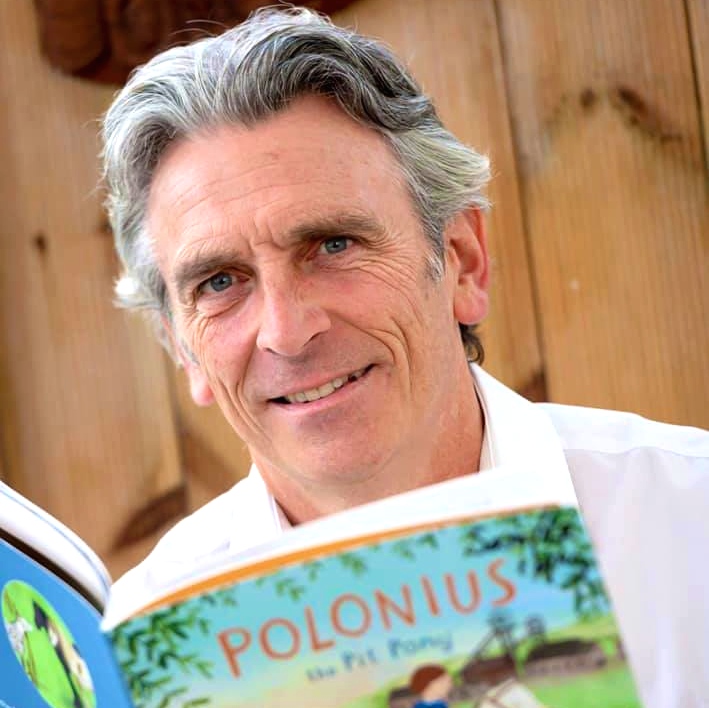

Richard grew up in a nomadic Romany Gypsy family among the coal mining communities of the North East of England, traveling from stopping place to stopping place and learning new skills from his family along the way. He’s worked across many fields, including (but not limited to) authoring children’s books, founding National Men’s Health Week, restoring antique furniture and working as a motivational coach for a professional football team.

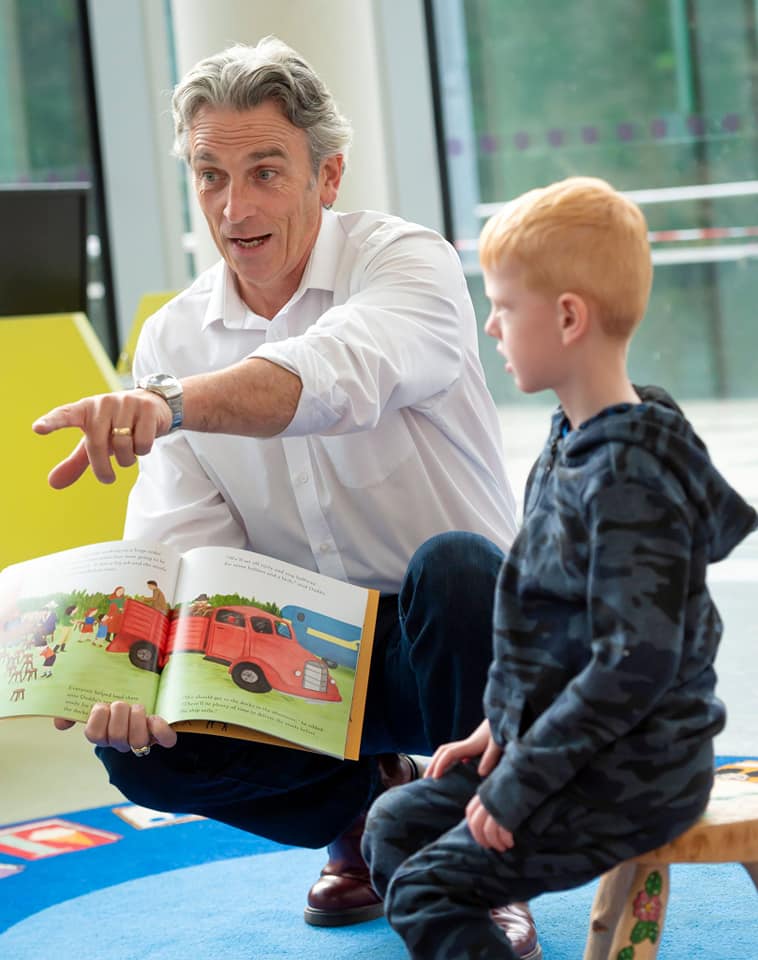

Through books, monologues and workshops in schools, Richard brings forward positive representations of Gypsies, Roma and Travellers. As he sees it, the most rewarding part of his work is to hear from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller children that they finally see themselves represented in books.

Richard is a captivating storyteller, with a wealth of raw material from his life and family history. Read on for his account of his early life, his path to advocacy and storytelling, and the lessons he’s learned from growing up in a nomadic Romani family.

RICHARD O’NEILL IN HIS OWN WORDS

I grew up in a fully nomadic family in the 1960s. When I was born in 1962, my family didn’t have any permanent stopping places. They were exactly the same as they had been in the early 1900s, in Victorian times, and the stopping places were still the same. The only difference was that they had motorized vehicles rather than horses and caravans, and then come the mid-60s, things were starting to change. There was a lot of construction work in England, but particularly in the North East of England. Towns were expanding; housing estates were being built—hospitals, schools—lots of things were built in the ‘60s, and a lot of our traditional stopping places were taken. When people would say, “Well, you know, these Travellers are here or there,” actually they just noticed us because we were in places where we hadn’t been before. And also, we were on the road with horses—now, I don’t remember this; this was my dad—but with horses it took them a week to get somewhere, so they weren’t camped up as long, whereas when you had a car or a van or a truck, you could get to that place in half a day or a day.

In 1968, in England, they passed the Caravan Sites Act, which meant that every local authority that had Gypsies and Travellers in their area (which was pretty much everywhere) had to provide a caravan site. You put your name down, but my dad didn’t want to be settled down. He wasn’t, shall we say, a traditionally educated man. He’d been to school, probably, he could count months in his life—in the winter of every year. He could read a little bit, he could write a little bit, but apart from that he had no education at all. He watched the cowboy films, which was one of his big things, and he saw the Native Americans, and he saw what happened to them, and he didn’t want to see us settle down.

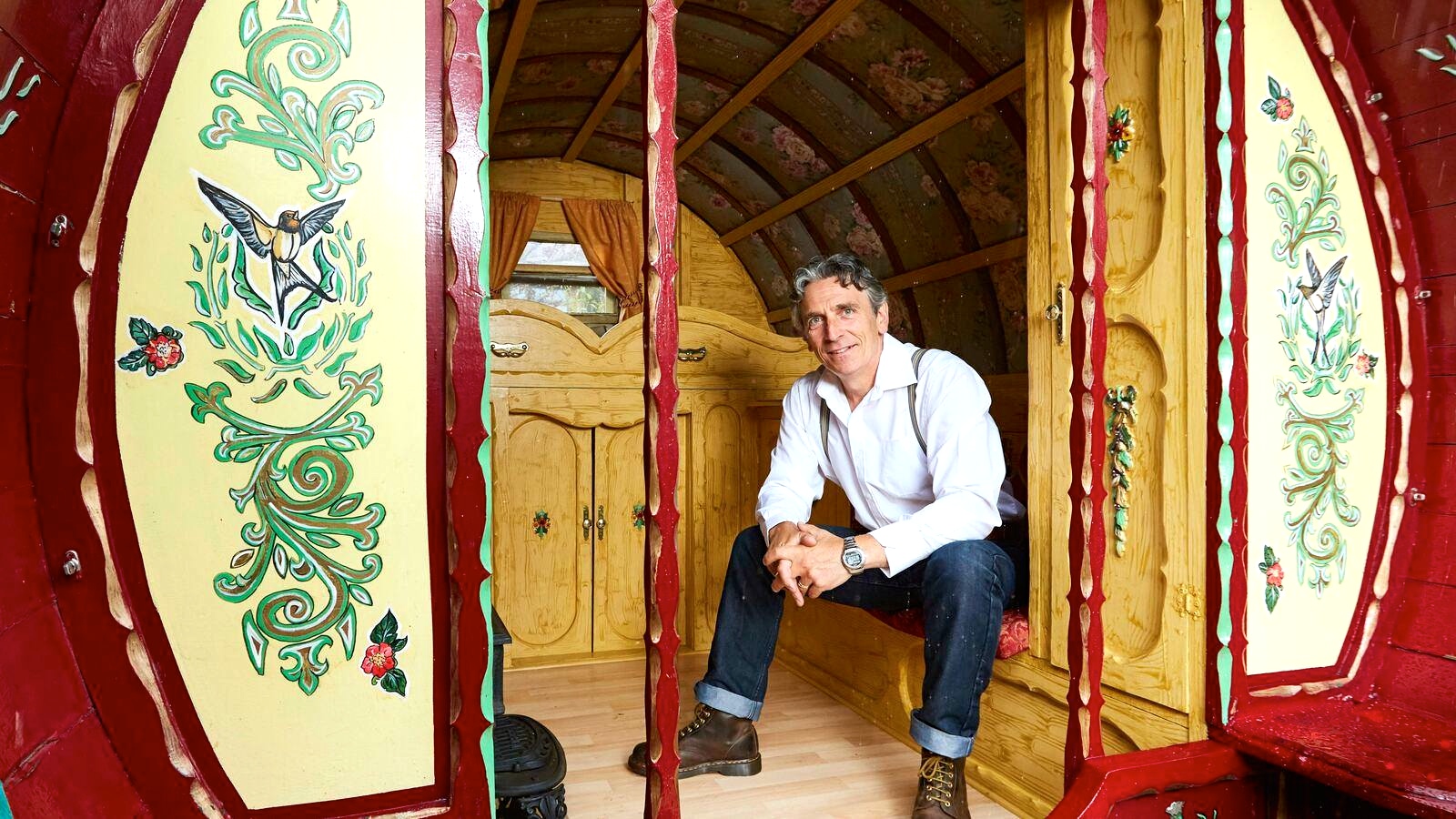

But in the end we ran out of places, and my dad had a business, so we had to buy a small house, and we lived in the caravans in the yard, and we used the facilities in the house. And that’s been my life ever since, actually—we’ve been in and out of caravans and houses. When me and my wife were married, we lived in a caravan, and then we lived in a house, and ultimately we lived in a block. God willing, I will end up in a caravan again.

I’m in a house in the winter, and because of my work—I’m moving around—I can spend some of the time in the caravan when I’m working. If I’m really lucky (which I was a few years ago), I can manage to have it parked up for six months on a caravan site, which was a farmer’s apple orchard, which she was slowly turning into a caravan site. To wake up every morning and see apple trees, and to watch the apples grow, gave me an idea for a book, actually, which is called Anna and the Apple Tree. So there’s a picture book out; so there you go.

I worked all the different jobs my dad did. We were collecting scrap; we repaired old furniture, antique furniture—very popular in the ‘70s—we sent a lot over to you lot. You had empty containers and stuff in ships, and you were just buying anything from the old country. Yeah, people used to come to our place, and they would buy it and take it to the port, and they’d have buyers, and they’d send it to America in these huge containers. So we did that—that’s where I learned a lot of my woodworking skills—and we worked on houses, which led me to the construction industry, which I did for quite a long time and really enjoyed it.

I’d always written. Even as a kid, I’d always liked words, loved words, and I was lucky because I was brought up with both languages: English and Romani. That was lovely, because at school we had English and teachers taught me how to write. I could read before I went to school—I taught myself to read by the time I was four.

[I did this] just by memorizing. Just by memorizing books. Yeah, by the time I got to school I could read. You didn’t start school until you were five. So I could read at four, and then I started reading one book and memorized it, and then read another and got to know the words. By the time I got to school at five, I could pretty much read anything. So they taught me how to write, which I’m grateful for, and I’m always telling children I was lucky.

As I got older, I was asked to do some work for Gypsies and Travellers. I’ve always been a campaigner for human rights, and I’m the founder of National Men’s Health Week. I’m always trying to help out every community I’m in. Because that’s the way I was brought up. Nobody in my family, nobody was left out; everybody was included. So I was brought up with those principles, and I’ve tried to live them wherever I’ve lived ever since.

People asked me to talk about some of the things I did as an entrepreneur, because I started one business, then started another. I did pretty good. So I was doing my human rights and stuff, and somebody asked me to go and work in professional football as a motivational coach, which I did, and that was quite easy in a way, because all I did was get that football team to act like a family. So they acted like a family—we cracked it.

It’s really interesting because these days I’ve come to coin it as the nomadic way, and it’s a set of principles, and it’s not just in this nomadic community that I grew up in. We actually not look at other nomadic communities around the world, and you can see, despite everything against them, we’re still surviving. Some of us, now, we’re looking outwards and using technology and working with non-nomadic people.

And actually, a lot of younger people like yourself have become more nomadic. This led me to go into a large company in Canary Wharf, up in London, with a colleague of mine last December and spend a whole day talking about this with ninety of their top managers—bright young things. And they just loved it, because they could see the storytelling rather than trying to sell people stuff, the clients they had, to actually tell them what you can do for them, tell them your story, tell them their story, and think more nomadically. And it’s really interesting, because this young woman afterwards—so smart, again, this millennial thing, people say “oh, snowflakes,” that’s ridiculous. Some of the smartest, most hardworking people you’ll ever come across are the so-called millennials.

And this young woman afterwards—because I was talking about how life is very circular, and I still believe everything is circular; there are very few straight lines in nature. There are some, but there are few. And when we set off, my dad taught us to work circular—start one place, you go around, and then you come back. We never went somewhere in a straight line; we went in circles. And I was talking about all of this, and this young woman afterwards, she coined the phrase—I don’t know who she is or else I’d credit her with it—she came up with this phrase afterwards when they were doing a plenary session, and she said, “circles move; lines drag.” She’s a genius. It’s not my phrase, I can’t claim it; it’s this young woman in this organization. Hopefully one day she’ll find it, and she’ll say, “I said that,” and I’ll say, “I can put your name to it now.” She really got it; she really listened.

So then, over in Leeds, the Leeds Traveller Education Service were doing quite a lot of work around Gypsies and Travellers, and they knew about my other work that I was doing as a volunteer—mental health and all sort of stuff. I’ve always been very aligned and very aware of where I come from. Even if I’ve been away from my family, my extended family, I’ve always been very aware of my roots and very proud of where I come from. That’s part of me and I would never change it. Even when I’ve lost out because of it, when people have said, “we don’t want him,” that wouldn’t deter me. And so they asked me to do some storytelling. I’d been to my daughter’s school once or twice to help out, when she was five, but I’ve always told stories to my kids, always made stories up, and I love stories—it’s how we communicate.

We, as Travellers, as Romani people, when we get together, we will—and all the people who have gone before us, like my dad, who passed away a long time ago, and my mum, and my grandparents—we talk about them in our stories, so we keep them alive. I could talk about something 200 years ago here with you now, and something that happened on Saturday with my grandson, who was at the Rochdale Literature Festival. He’s seven now, my grandson, and it’s so cool, because we were there, and I’d been working with a school, and there’s a lot of school kids here at this festival. And I said, “This is my grandson, Tommy,” and they said, “What, he’s real—isn’t that the one you told the stories about?”

So I started working over in Leeds, and I thought it would just be a one-off, and actually I really enjoyed it. They really enjoyed it, and more schools kept asking me. And I thought, “I really like this.” So they came up to me one day, about a month in—we’d done a few bits and pieces—and they said, “What’s the plan with this?” And I said, “There isn’t any plan; I’m just enjoying the ride until it stops, but it hasn’t stopped yet.” So I just kept expanding and expanding my work, finding out what teachers wanted, finding out what curriculum is all about, which I didn’t know. And I’m still in awe of teachers now. I don’t go to school and just do stuff—I liaise with the teachers and find out what they want, what their targets are, how I can help. And, you know, it’s working.

And then about four years ago I was at an event, doing some storytelling at a university, down in London, on a Saturday. It was about diversity and inclusion, and there was somebody there from a publisher called Child’s Play. They got in touch with me and said, “Have you got some stories you could send us?” Which I did, and there we are. So we’ve done these four lovely books, brand new one out this week. It was really interesting because I’d got the books in just in time for the Rochdale festival, and Michael Rosen, who is the former Children’s Laureate, was there at the festival. We got chatting, and he bought the book. He bought that new book, so he was my first customer. That was so nice of him to do that.

In between times, [there was] a project going—it was called Wide Open Spaces. It was about people from different backgrounds in the countryside, and I managed to get onto that. There were eight of us, and we produced a monologue of 2000 words, and the idea was that it would be turned into a performance of all of them, and then five of them would be selected to go onto Radio 4. Mine was one of the five, and that was in 2006. So I’ve been writing ever since, as well as the children’s stuff, and recently, last year, I did some work in Budapest with the Independent Theatre Company, which was absolutely amazing, just brilliant people. Then they’ve got the Roma Heroes book out, which is the anthology. So yeah, it’s sort of gone in a big circle. I’m just so pleased to be able to do books, to do the storytelling, and to see things changing slowly.

Sarah: What changes would you say you’ve noticed, say, between when you were growing up and now?

I would say that people of your generation are a little bit more open. I think they see the Romani culture. I think they can make the distinction between some of those bad Travellers who cause problems and people like myself and Irish Travellers. There are lots of fantastic Irish Travellers doing great work all over the world, and many of them are my friends, who are just trying to do what they’re doing, and we come from a particular community that has got some problems in it, like every community has. I think your generation can distinguish. I think you find very old people, who are probably in their eighties—they are pretty good because they remember some of the older people. And then you’ve got your generation who, like we talked about before, can see the benefits of some of the things in our culture and the arts that are coming through.

I think there are quite a few people in the middle, who have watched too many TV programs and believe them. So yeah, I think things are changing. These things are always slow. It’s bizarre when you think about it, that the books that we’ve got out now—when I was at school there were no books like that. And it’s taken 50 years. It’s taken 50 years. I don’t want a boy or a girl to be in school today thinking, “You know what, I’m not going to bother reading or writing because there’s no books that are like me”—to feel excluded. That’s why I launched this year Diverse Book Week, with no funding, hardly any time because of all the other stuff I’m doing. But we reached out to people, and people responded, and I think next year’s going to be even better.

We had this stall, this little stand, like a circular table, and my publisher, Charles Blake, sent me a load of books for free, and the idea was that they’re not for sale, they’re just for people to look through. After the festival on Saturday, they were to be given away to the local communities. And I’ve got this wonderful photograph—I tweeted it, I think, this morning—and it shows a mum with a little baby in the buggy. I actually was just coming back from somewhere because I couldn’t man the stall all day, and I came back, and there they were, crouched down at that stall, and the mum is reading the child this book. They’d just been drawn.

I kept saying to people, to the children particularly, “Come have a look at these books. Is there anyone there who looks like you?” And this girl’s like “Yeah!” And her brother goes, “That one looks like you!” And it was just so wonderful. You can’t quite explain what it feels like to see yourself in books.

There was a girl—she was going on six—at a school this year in Yorkshire, and she saw me at assembly talking about books. The teacher said she just couldn’t believe it—this is 2019—she couldn’t believe that there was someone from her community just up there talking about books. Anyway, come dinnertime, she has her lunch, and then I go to her class, first class after lunch. She comes up to me, and she gives me something, and it’s an A4 sheet of paper folded in half. She’s written in it—she’s not quite six—you can understand everything she says, and the gist of it is: “I saw you in assembly. I did not know you were a Traveller. I like”—and then she’s put “like” and crossed it out and put “love your books. I am a Traveller as well.” It’s so wonderful.

The books have gone all around the world. They start conversations. Teachers use them in schools to explain certain things. So yeah, I’m very, very happy. So if we can just keep that going.

I belong to a union called Equity, in England. It’s the actors’ union, and I’ve been a member for about eleven years, and I’m one of the few—there are some of us—there’s a few Romani people: dancers, singers. And I’m just trying at the moment, they have promised me that they will do a feature on me, and I will end up being the first Romany in that magazine. They’re trying to organize a symposium at the moment, because we need to get more Roma young people into the arts, but if there’s no opportunities for them to work—there’s nothing happening—they’re not going to do it.

It’s really strange, because when you think of some of the famous Romani people—we’ve had Charlie Chaplin, in particular: Mr. Showbiz. But again, he had to go to America. I don’t want our young people to be having to go anywhere. It’s crazy—I loved every minute of it and I would go back there again tomorrow—I’ve been to Budapest two consecutive years with the Independent Theatre Company, and they’re just the best people. Rodrigo, he’s like my brother. He runs the organization, and we shared our story one day, and our stories are very similar. We both lost our dads when we were quite young—I was 21; he was a little bit younger—and we share a lot, Rodrigo and I. But I shouldn’t have had to go to Budapest, which, you know, has one of the worst anti-Romani presidents, perhaps. And yet I had to, to get my stuff on stage. I had to go to Budapest. This should be done in London and Manchester.

Sarah: What do you think is preventing it?

I think it’s the same thing that’s preventing working class people from getting through. I think there are people who are gatekeepers, and I think they don’t want people like me, and they don’t want people like working class folks, and they don’t want us because we’re not in their clique. What I keep saying—and I want the Arts Council to look into this—is that if you are receiving public money, you cannot discriminate. Private money—choose whoever you want. But they should—and this is what Equity are trying to do now—they’re trying to look into and see how much of this money that we’re getting is going to Roma. We’re a big community; we’ve got a long history; Shakespeare knew about us.

This is the best way to explain it at the moment: if I went along to a production company and then to a broadcaster like Channel 4, Channel 5 and said, “Look, I’ve got this idea for a program. I want to call it ‘The Asian People Next Door.’” “What? Can’t do that! That’s terrible!” You go along, you say “The Gypsies Next Door,” and you can get it on mainstream TV. That’s where we’re up to. BBC: Why aren’t the BBC helping us out with creating? We’re very funny people. I go to schools, and a lot of the comments are: “That was the funniest story.” We have Citizen Khan on the BBC—brilliant, fantastic, wonderful. Where’s ours? Why are we constantly left out? It’s not on. So that’s what I want to happen, and I’m afraid, unfortunately, we’ll have to shame these people into it because they’re just not going for it. So I’m hoping that’s what we can do.

Interview by Sarah Zawacki with Richard O’Neill in Bury, England, July 15, 2019.

You can find Richard on Twitter, and on his website.

For more about Diverse Book Week, see here.

For more about Independent Theatre Hungary, see here.